Image by Dh. Aloka

- Bowing to Manjughosha’s Mind, Speech and Body

To you whose wisdom

Purifies like a cloud-free sun

The veils of passions and of ignorance,

Yielding perfect clarity;

To you who sees all matters as they are,

And so holds the book

Of Prajnaparamita to your heart,

To your mind, Manjughosha, I bow.

To you whose kindness

Views each being as your only son,

Covered in avidya’s darkness,

Afflicted in the prison of time;

To you who utters the sixty-four-fold voice,

Resounding loud as thunder,

Rousing from passion’s sleep,

Shattering karma’s prison fetters,

Dispelling avidya’s darkness;

To you who grasps the sword of wisdom

To cut every shoot of duhkha,

To your speech, Manjughosha, I bow.

To you whose perfect body-of-virtues,

Chief among the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas,

Always pure, yet completing the Bodhisattva path,

Adorned with one hundred and twelve blazing ornaments,

Dispersing my mind’s darkness,

To your body, Manjughosha, I bow.

- Manjughosha mantra, and offerings

2. Praise of body

O Manjughosha, treasure of wisdom,

Please for one moment consider

These flowers of verses of praise

Quivering in the wind of faith,

O radiant mass of rays of saffron light,

Like a golden mountain

Embraced by the rays of the rising sun.

Your mountain body is tall and stable,

Your skin is pure and clear

Like soft dust of gold.

Your long, lustrous black hair

Is bound in a knot

And five gem-adorned crests,

Above a brow like the waxing moon.

Your eyes are long, and blue as utpala,

Your mouth is smiling and well-pleased.

From your fine ears

Dangle gem-adorned earrings,

And you wear many other ornaments.

Adorned with armlet and bracelet

Your right hand holds the sword

That cuts the root of the tree of materialism.

Your left hand holds to your heart

The supreme volume

Of exact and full teachings

Of the sole doorway to peace.

Your robe of silk shimmers

And is hemmed with tinkling bells.

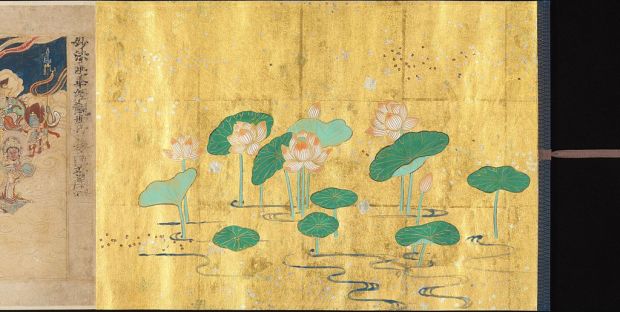

You sit in vajra posture

On moon disc, and the saffron centre

Of a six-petalled lotus.

Like the thousand rayed sun

Plunging its seven horses

Into the golden ocean,

Your body everywhere shines.

When I behold your body

I weary of my long wandering.

May my erring mind

Come into the spirit of Enlightenment.

- Reading

- Praise of Speech

O Manjughosha, Lord of sweet speech

Your many voices fill all lands

In every different language

Like a crystal prisming all colours,

Satisfying all living beings.

The melody of your speech

Is like a sphere of music,

Outlasting all the Samsara,

Releasing from sickness, age, and death.

It is pleasant, gentle, heart-stirring,

Harmonious, stainlessly clear, and sweet.

It is not rough, very calm, painless,

And satisfies body, mind, and heart.

It is rational, relevant,

Free of all redundancy,

All-informing, totally illuminating, enlightening.

Its rhythm not too fast or slow,

Its tone sweet, penetrating everywhere.

Its phrases are complete and confident,

Pervaded with joy and insight.

Emerging victorious, it dispels the three times.

These are some of the qualities

present in each and every utterance

Of your Brahma voice.

Not too loud when near,

Not too faint when far,

As if it manifests from the sky

Like the thunder in the rain-cloud

Girt with its belt of red lightning.

Just by hearing your stream of speech,

The receptive accept it,

Condemning wrong discourse,

May I never be parted from hearing your speech!

- Manjughosha’s teaching

O Manjughosha, Lord of Dharma,

Certain of the true colour

Of all that can be known

May you grant superlative wisdom

As the supreme refuge.

Not one phenomenon

Is hidden from you,

Thus you never exceed just proportion

In the training of your pupils’ faculties.

You see how sharp or dull are their abilities,

In faith, memory, samadhi and so on,

And so yours is the highest skill

In teaching Dharma.

Since you know entirely

The spiral path

And the Transcendental path,

And the way that leads

To states of misery,

You are the best spiritual friend

Of living beings.

Please grant the supreme instruction

Of the Buddhas!

The elephant of my mind

Is hard to tame,

As it runs amok

In the jungle of unconsciousness.

It is drunk on the liquor of materialism,

Knowledge of right and wrong forgotten,

Wrecking the trees of virtue,

Dragged by the chains of existence’

Losing the female elephant of success.

I should bind it with the rope

Of conscience and mindfulness,

And guide it with the goad of true reasoning

Onto the good Aryan path,

Trodden by millions of supreme sages.

With tireless effort on that path,

By meditating again and again

Without giving up,

I shall reach the Vajra-like Samadhi,

And the mountain of extremisms

Shall be rendered merely a name.

- Reading: The Song of the four mindfulnesses. (A teaching said to have been received by Tsongkapa from Manjughosha.)

4. Praise of mind

O Manjughosha, lord of Wisdom

Just as the king of eagles

Soars in the heavens,

Your mind stays neither in existence

Nor in peace.

By praising your mind,

May I never part from the wisdom

And love of Manjughosha.

False appearances entirely conquered,

You dwell in the chief of all samadhis.

By your power over appearances,

And your clear knowledge of all experience,

You enter the ultimate realm.

Like a poison tree whose root is destroyed,

And the seeds of all habits eradicated,

how could you ever deviate, O refuge,

From the Dharmakaya?

Though you never leave the ultimate realm,

You know individually in every instant

The vivid appearance of many objects,

Like a rainbow, or reflections in a mirror.

Your direct vision, free of all veils,

Sees the Nirvana that ends defilements,

And its means, the eightfold path.

Thus you are the best of all refuges.

Long you practised the goal of compassion,

The sole path of all victors,

The entrance to the battle

Of the hero Bodhisattvas.

Loving one, you see the errors

Of forsaking others’ happiness.

You never allow suffering to continue,

And are never content

With the most alluring of pleasures.

By your long cultivation of Bodhicitta,

Seeing the equality of self and others,

Practising the exchange of self and others,

You hold all beings as yourself.

- Svabhavashuddha mantra –

5. Aspiration

Though seeking desperately,

I find no good refuge other than you.

Turning to you, my mind

Feels like a sunburnt elephant

Plunging in the lotus pool!

Having attained an infinite store

Of samadhis and doors of liberation,

May I manifest limitless bodies

To see the Jinas

In a million universes.

Then, having reached the limit of wide learning,

Satisfying limitless beings

With the Dharma,

May I before long attain

The supreme body

Of the chief of jinas, Manjughosha!

Obtaining supreme understanding,

May I cut off the doubts

Of all living beings.

Never transgressing your instructions,

Through devoted, one-pointed practice,

May I quickly gain mastery of speech.

With the vision that belies all extremism,

And the compassion that sees all

As my only child,

May I lead all beings

Onto the supreme vehicle.

Remembering all teachings,

Able to answer all questions,

May I spread out the feast

Of eloquent Dharma.

By the glory of the mind of Manjughosha,

Who, without calculating,

Fulfils the hopes of all,

May I become like you,

As beautiful as the autumn moon,

Whose sweetness fills the limitless sky.

- Concluding mantras

Ratnaprabha, compiled and re-rendered September 1994, at Guhyaloka retreat Centre, Spain.

The first part is a revised version of the traditiona Manjughosha Stuti. The rest is all adapted from Tsong Khapa’s ‘Cloud Ocean of Praises of Manjushri’, in Thurman, R., ed., Life & Teachings of Tsong Khapa (Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamasala, 1982), 188-197.

As he lay on his deathbed between the twin Sal Trees, the Buddha’s parting words were: “Be your own light, be your own refuge, the Dharma is your light and refuge. Things naturally decay: win through by mindfulness!”

As he lay on his deathbed between the twin Sal Trees, the Buddha’s parting words were: “Be your own light, be your own refuge, the Dharma is your light and refuge. Things naturally decay: win through by mindfulness!”